When faced with something complicated or politically sensitive, some judges hide behind process arguments. That has already happened with regard to the Kari Lake v. Katie Hobbs election complaint. Judge Peter Thompson of the Maricopa County Superior Court dismissed part of the case based on an ill-fitting process argument: laches (filing too late).

In early December, Kari Lake filed an election complaint comprising ten separate claims, but His Honor threw out several, including the strongest one: the claim that thousands of ballots were processed with mismatched signatures (complaint pg. 13). Judge Thompson ruled that Kari Lake was objecting to long-established procedures (and not to recent violations of those procedures), so she should have made her objections much sooner. His reasoning does not jibe with the facts.

The Kari Lake lawsuit correctly indicates that Arizona law (A.R.S. § 16-550) prescribes a two-step process for validating early ballots.

The Recorder or the Recorder’s designee must “compare the signatures thereon with the signature of the elector on the elector’s registration record.” If there is a match the ballot is accepted.

“If the signature is inconsistent with the elector's signature on the elector's registration record, the county recorder or other officer in charge of elections shall make reasonable efforts to contact the voter, advise the voter of the inconsistent signature and allow the voter to correct...”

Based on the sworn statements of three whistleblowers, the two-step procedure prescribed by law was not followed. Instead of attempting to contact the voters to have them “cure” their signatures, the “level two managers” simply reversed the signature rejections of the level one workers, or made them re-process the signatures until a different result was obtained.

Kari Lake states that Maricopa County had 32 employees performing signature verification and/or ballot “curing.” Three of the 32 workers were “whistleblowers” who made disturbing claims in sworn declarations. Here are some of the statements of Andy Myers, one of the three whistleblowers. His job was to “cure” signatures that did not seem to match registration records (complaint pg. 17):

“The math never added up. Typically, we were processing about 60,000 signatures a day. I would hear that people were rejecting 20-30% which means I would expect to see 12,000 to 15,000 ballots in my pile for curing the next day. However, I would consistently see every morning only about 1000 envelopes to be cured. We typically saw about one tenth of the rejected ballots we were told we would see.

The most likely explanation for this discrepancy is that the level 2 managers who re-reviewed the rejections of the level 1 workers were reversing and approving signatures that the level 1 workers excepted and rejected. ...”

Myers concluded: “...the level 2 managers were changing about 90% of the rejected signatures to accepted.”

The other two whistleblowers made similar declarations, except they saw rejection rates that were even higher: 35 to 40%. Most of those rejected signatures were supposedly cured, without contacting the voter. Whistleblower Yvonne Nystrom felt she was being pressured to approve signatures because they were being re-processed even though they had already been reviewed at all levels (complaint pg. 18):

“These 5,000 to 7,000 ballots had already been through the full level 1,2, and 3 process and [had] been rejected. Therefore, I do not know why [we were] going through them again, and that is why it seemed that Celia wanted them approved.”

The third whistleblower, Jacqueline Onigkeit, seemed to suggest that the curing process was out of control (complaint pg. 19):

“In order to perform the curing process, we were given a batch of stickers to place on a ballot... One of the problems with the stickers was that nothing prevented a level 1, 2, or 3 worked (sic) from requesting a massive amount of ‘approved’ stickers and placing them on ballots. Again, observers did not watch any level 3 work and did not watch most of level 2 work. Once stickers were placed on ballots, there was no record on the ballot or elsewhere to determine who placed the sticker there.”

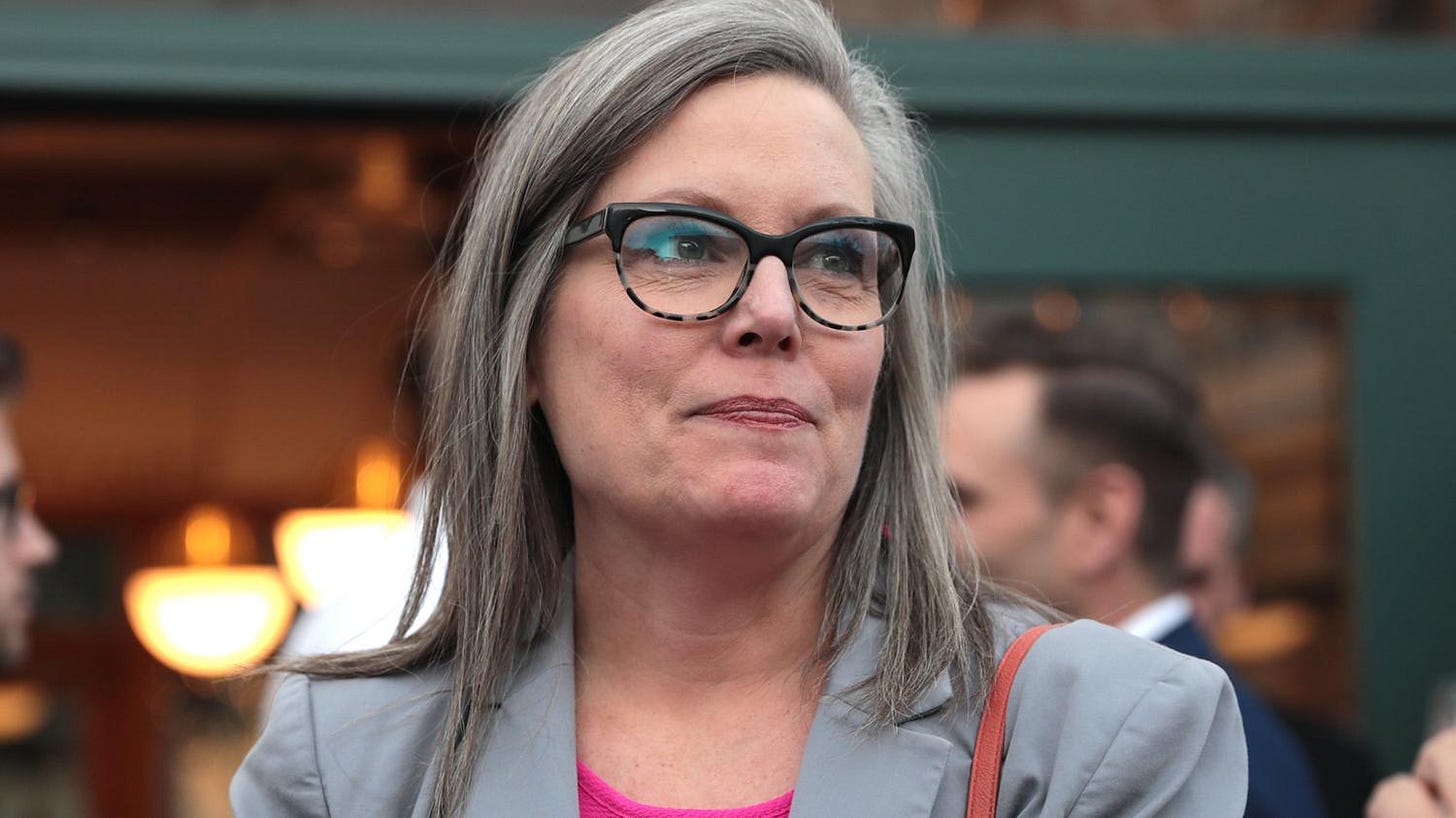

The bottom line is that the two-step process, prescribed in the Code, was being ignored or abused. Instead of contacting voters (the second step in the process), level two managers just reversed the level one reviewers, or forced them to keep repeating the first step. If that is the case, Katie Hobbs was not necessarily elected by the people of Arizona— rather, she was elected by “level two managers.”

In her response (pg. 9), Hobbs created a straw man: “This claim apparently rests on Plaintiff’s presumption that a voter’s ‘registration record’ is narrowly limited to a voter’s registration form....” However, there is no such presumption in the Lake complaint— stated or implied. Hobbs simply made that up, and added the word “apparently” to soften the subterfuge.

The Hobbs legal team was probably “high fiving” when they learned that Judge Thompson actually believed their little artifice. He bizarrely cited Kerby v. Griffin, 48 Ariz. 434, 444-46 (1936) as a basis for dismissing the claim (Under Advisement Ruling, pg. 7):

“[P]rocedures leading up to an election cannot be questioned after the people have voted, but instead the procedures must be challenged before the election is held.”

In other words, he accepted the Hobbs claim that Lake was quarreling with the established procedure for verifying signatures. If the judge had read the complaint more carefully he would have realized that Lake was pointing out, based on the whistleblower statements, that the law had not been followed.

This ruling has greatly damaged the ability of Lake to win her case, and it raises concern regarding this judge’s ability to fairly adjudicate the remaining claims.

However, if Lake does not succeed, let me be the first to say: Congratulations “Level Two Managers”! You successfully elected the next governor of Arizona.